Alumni Perspective: April Pruitt BA’14

April Pruitt BA'14 helped bring vintage video games back to life for the National Videogame Museum in Frisco, Texas.

April Pruitt BA'14 helped bring vintage video games back to life for the National Videogame Museum in Frisco, Texas.

Editor’s Note: This first-person article, “Game Not Over,” appeared in the spring 2016 issue of UT Dallas Magazine.

Videogames: Before they were in our pockets, they were on our televisions and before that, they were in a dark arcade room filled with sights and sounds that are still part of our culture. They are the media that combine art with technology.

In 2014, I completed a degree in interdisciplinary studies with a focus on art and technology and business management. I was an older student, getting my education and raising a family at the same time.

I felt a little out of sync with some of my younger classmates. For instance, the games of my youth were Galaga and Pac-Man — often played in arcades where I tried to progress through the various levels while getting the most play from a 25-cent investment on a console without a pause button.

Many who grew up with modern games like Portal and Halo just didn’t understand the attraction to the arcade games.

Fortunately there were enough fellow classic game enthusiasts at UTD to found a club for those with similar interests.

My goal after graduation was to work in the animation and videogame industry. Little did I expect that I would be re-creating an arcade from the 1980s, an adventure that began when I read that the National Videogame Museum would be established in Frisco, Texas.

When I reached out to museum founders Joe Santulli, John Hardie and Sean Kelly to offer my help, it turned out that they were just as excited to hear from me since they needed help getting more than 40 different games ready for regular play.

Joe, John and Sean provided a storage locker full of classic arcade games (some of which are more than 50 years old) including Computer Space, the original dedicated Pong, Galaga, Centipede and Q-bert. Most were in rough shape and would need work both inside and out.

“It was overwhelming, but I love a great adventure, especially if it involves technology.”

Because the average game weighs over 300 pounds, I enlisted the help of my husband, Jeremy, who has some amazing woodworking skills.

We began working in the storage locker because the museum’s building wouldn’t be ready for several months. In the hot Texas sun, we pulled games apart, taking out heavy CRT (cathode ray tube) monitors that hold a 10,000-volt charge, whether plugged in or not. It was overwhelming, but I love a great adventure, especially if it involves technology.

The Frisco Discovery Center was eventually ready for the museum to start moving in. The move allowed us to continue making repairs, but in a climate-controlled, powered, and safe environment.

After moving the games into the museum, Joe, Jeremy and I visited a local arcade auction and were fortunate to find a number of other games, including the power couple themselves — Pac-Man and Ms. Pac-Man.

Repairing classic videogames is a complicated task. Each game manufacturer has its own way of building arcade games, from the main printed circuit board to the cabinet holding it.

Several main components are included in all the games: the monitor, main game board, power board, and power brick. But these items may be presented in completely different ways in each game.

For example, Missile Command has only one board for the main computer with audio built onto the power board, but Spy Hunter has a four-board stack for the main computer and smaller boards mounted all over the cabinet, for a total of 12 different circuit boards.

The technology for game display also varies. Some machines, such as Asteroids, are vector based, meaning that the scene is drawn on the y rather than having a picture move across the screen. These complex games require a special vector monitor and specific testing equipment for the boards.

The bulk of my job, though, was not patching wires but conducting research — a lot of it.

For board repairs, I needed to locate technicians for each manufacturer. Many of the technicians are engineers whose hobbies include classic videogames. Someone who regularly repaired Atari games, such as Space Duel, probably wouldn’t have the expertise to repair Taito’s Zookeeper.

I was fortunate to have my husband’s help with the sometimes months-long quest for technicians, as well as handling shipping the boards for repairs.

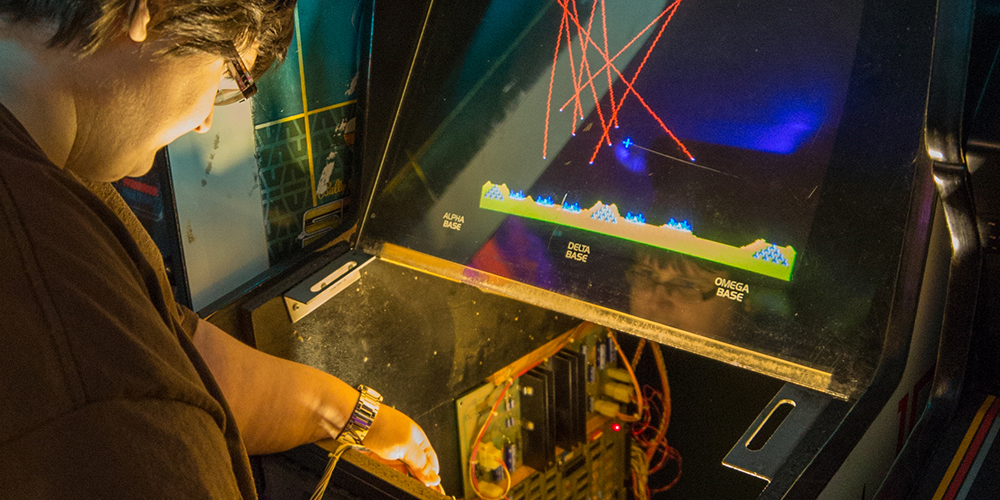

Pruitt takes a look at one of the arcade games.

Pruitt takes a look at one of the arcade games.

Besides pulling monitors and other support boards that often needed 30-year-old capacitors and other components replaced, I repaired unfortunate wiring congratulations made possible by an abundant use of electrical tape or even duct tape. I never knew what I would find in a machine, since many had been on location in bars or stuck in a barn for years.

The new home for these classic games, the National Videogame Museum, is the first of its type in the U.S., dedicated to preserving the history of the videogame.

The 10,000-square-foot facility includes interactive exhibits for electronic games of all kinds, including handhelds, consoles, and the area where I devote the most time — a replica arcade from the ’80s. Every time I am at the museum, I experience a feast for the eyes.

A black light responsive theme created by a local artist includes a sculpted foam centipede that appears to come out of the wall, providing an authentic arcade feel. Local artists also created murals throughout the museum depicting video game characters ranging from Mario to Lara Croft.

Interactive exhibits about the history of videogames include the world’s largest Pong and Super Nintendo controllers with buttons that are the size of an adult hand. Little-known gaming systems are displayed throughout.

Collectible promotional items — stuffed dolls, hats, keychains, patches and even cereal boxes — fill display cabinets. And thanks to donated furniture from well-known game designer and producer Randy Pitchford of Gearbox Soware, visitors can see a replica of his office.

Working in the museum is an amazing experience, one that I will remember for a lifetime. I am grateful for the opportunity to bring these classic games back to life.

Tags: Alumni